Through Confusion and Conversation

The subtext comes from a Frenchman who, like all French, learned and grew up as a manufactured product of the French Revolution.

Although they may have had monarchies and emperors since the Revolution, Jacques saw the big picture.

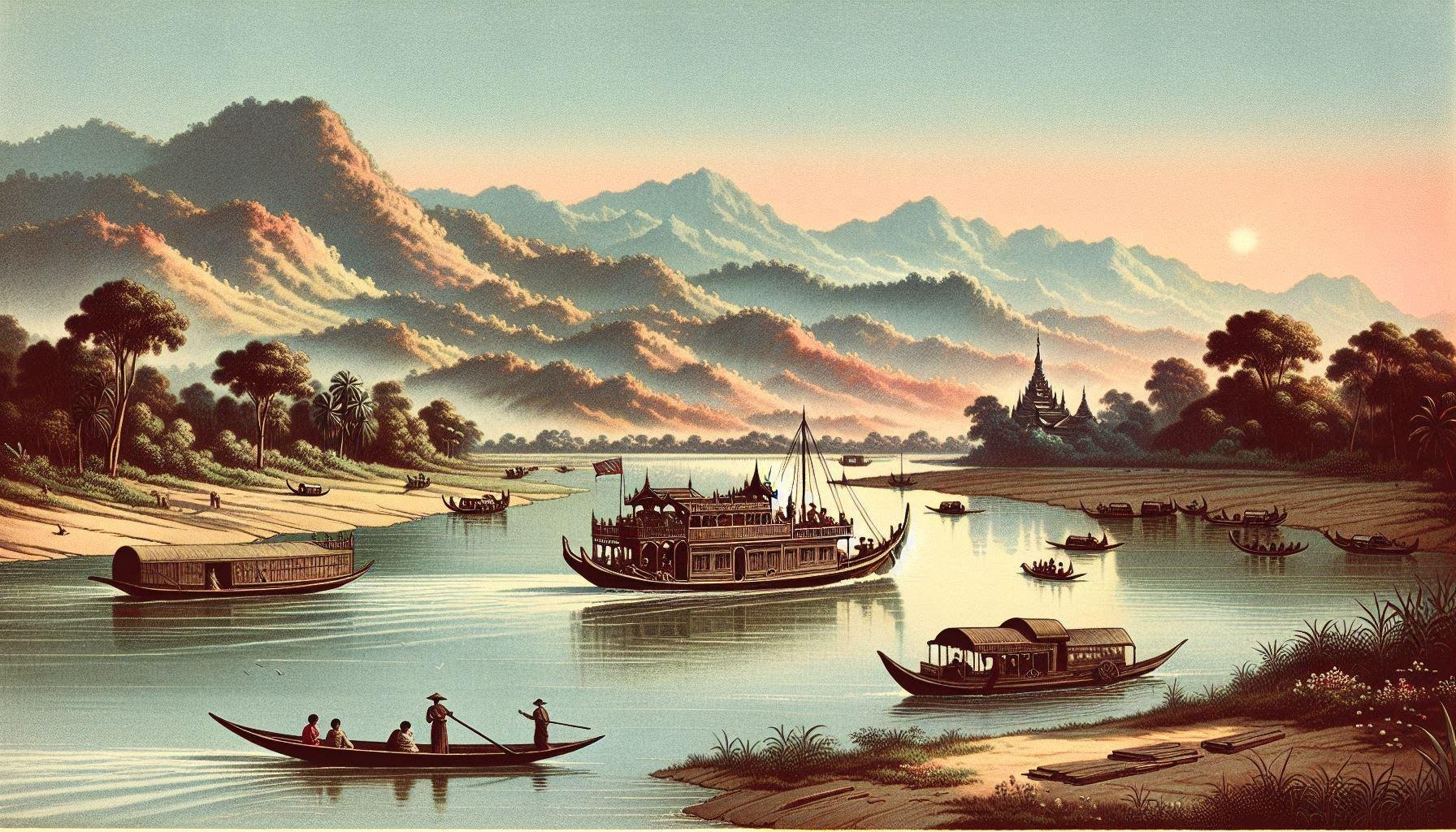

These views of rivers and nature collided with political expectations that only made them sweatier, but not the local soldiers, once again, busy playing cards, smoking tobacco, and seeming indifferent to their climate. However, a change in the climate was coming for Jacques, and the diplomat opened up about his whole life story. From growing up in East Anglia, learning the piano at a young age, reading both the Aeneid and the Odyssey as a youth, yet looking at Asia through his Greco-British lens. Jacques saw differently, viewing the fishing boats and many boats passing by them as they came closer to the kingdom of Siam, between a naval power and an allied nation. On one side, Britain, and the other side, the French. His ancestral countrymen if he never swore service to Britain, though Jacques laughed at this thought. France was serving Britain.

Allied they were, the French were virtually powerless without Britain's navy and wealth. He'd hear the arguments for and against Britain in Marseille or on trips to visit France, but without Britain, France was alone against those Prussians and Austrians. Jacques apologized for laughing out of turn; it was a funny memory of childhood. The diplomat believed Jacques and eventually retired from this conversation. He missed England. He assumed with enough willpower, he'd be this adventurer, the very one he idolized in literature. He thought he could brave the dangers and dismays of the world. Alas, he remained that wonderstruck boy with a wanderlust imagination. Jacques offered him a tobacco cigarette and told him it calmed his nerves. He had a major job on his shoulders.

They arrived in Siam with curiosity and some hostility. The people changed like seasons. Perhaps to Jacques, the culture of the people changed. The language sounded different, dissimilar to what the soldiers spoke, equally bemused and somewhat intrigued by Siam, yet like Jacques and the diplomat, they remained at their posts. Jacques was not afraid of translating to the French, putting great pressure on the Siam regime, as were the British, these European pincers that pinched Siam like some crab. They docked at a majestic palace, greeted not by a Siam official but by a well-dressed Frenchman, wearing clothes not suited for the climate, unlike the diplomat and Jacques. Jacques and the diplomat were greeted in French, not English, so perhaps an assumption was made that there was no need for any English. Jacques translated quickly for the diplomat, suddenly placed in this role with little preparation or adjustments.

While all disembarked, Jacques noticed how the locals put their hands together and almost curtsied, their language so tonal, like taps on the eardrums. Jacques mimicked the custom, except the Frenchman flicked them away, bothered by their intrusion. He commented to Jacques, while the diplomat looked around with intrigue, how the French could unite this uncivilized kingdom governed by superstition and age-old traditions, yet Jacques could sense a deeper context. The subtext comes from a Frenchman who, like all French, learned and grew up as a manufactured product of the French Revolution. Although they may have had monarchies and emperors since the Revolution, Jacques saw the big picture. Ideas, not men nor women, changed the world, and France, if rulers of Siam, sought to implement their ideas into Siam. The diplomat interrupted their murmuring, curious about the local teas or beverages to cool the old melon between his pricked ears.

The Frenchman suggested he retire first and, afterward, explore the palace with a guide. Jacques also noticed French soldiers, some conversing with those dismissed locals, but others looking unsuited for the climate, just like the Frenchman, wiping his brow with a handkerchief. Taken into the palace, Jacques and the diplomat marveled at the architecture while the Frenchman spoke in French about Siam, how venerated it was among the commonfolk, yet veneration did little against titanic forces, which brought him to a new interest. The negotiations between the diplomat and the French in Siam. There was some tension in the Frenchman's words, Jacques accurately detecting tone in translation, a key component of any worthy translator, as he translated for the diplomat.

The diplomat grew quiet, mulling his next words. He then spoke. He needed to be alone.